Interview with Prof. Sandy Frieden: The Cinematic Mastery of Douglas Sirk in the 1950s

Sandy Frieden, Ph.D., will join WIH from April 16 – May 14 for a five-week course titled Tearjerkers of the 1950’s: Films of Douglas Sirk.

Renowned for his melodramatic narratives and visually stunning compositions, Sirk’s work continues to captivate audiences and scholars alike, offering profound insights into the socio-cultural landscape of post-war America. In this exclusive interview, we delve deep into the brilliance of Sirk’s directorial prowess with Prof. Sandy Frieden, whose expertise sheds light on the thematic richness, visual symbolism, and enduring relevance of Sirk’s cinematic oeuvre.

WIH: Everyone who has taken your classes, says that you are truly passionate about film and teaching and do a spectacular job! What is it about the film genre that captures your imagination?

Prof. Frieden: I love being immersed in the world of a film, identifying with characters, getting swept up in their lives on screen…and then I love analyzing them, figuring out exactly how the film does this to me.

WIH: What do you hope your students will take away from this class?

Prof. Frieden: Some students say they worry they won’t be able to look at a film the same way anymore, but understanding how a film works doesn’t take away from the film at all. Just the opposite—the film you love becomes even more amazing because you notice so much that you missed. Really great films stand up for multiple viewings, and every time, you notice something that you missed before.

WIH: What makes Douglas Sirk stand out to you as a filmmaker?

Prof. Frieden: Sirk works like a magician: he pulls in huge audiences who love his films and remember them for years…and at the same time, under the radar, he’s critiquing American society and values of those same audiences who are crying in the aisles.

WIH: Sirk’s films have undergone critical reevaluation over the years, particularly in terms of their depth and complexity. How have perceptions of his work evolved, and why do you think his films continue to resonate with audiences today?

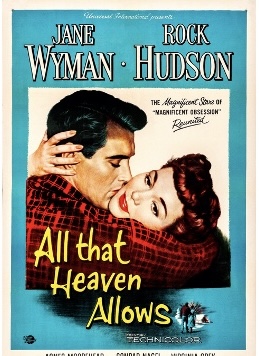

Prof. Frieden: Sirk’s films from the 1950s were considered weepy melodramas at the time and drew in huge audiences to identify with the big stars who had big problems (and who almost solved them). Later generations of filmmakers looked again at his films and admired the way he was able to communicate uncomfortable messages while still keeping a firm grip on the hearts of his viewers. Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven and Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water are both remakes of and tributes to All That Heaven Allows.

WIH: Sirk’s films often explore themes of class, gender, and societal norms. How does he approach these themes, and what messages do his films convey about them?

Prof. Frieden: Glamorous stars playing roles in which they fall in and out of love and bump up against restrictions, social rules, class differences—we can identify with their longings and perhaps also notice what the barriers are that restrain them. And if we notice, then perhaps we can fix them.

WIH: How do you think studying Sirk’s films can contribute to a broader understanding of cinema and its cultural significance?

Prof. Frieden: Paying thoughtful attention to any film helps us understand all films better. I love popular films because (besides hopefully being enjoyable to watch!) they reflect what our own values are as a society—for better or worse. And I especially love watching them with other people so that I can notice different reactions—maybe I’m out of step with the viewers around me, and I need to ask myself what that means!

WIH: Sirk’s collaboration with actors like Rock Hudson and Jane Wyman is well-documented. How do these collaborations influence the themes and character dynamics in his films?

Prof. Frieden: Leading directors have often worked repeatedly with certain actors to build on the rapport they’re able to develop over multiple films. Also, the charisma that certain actors bring to the screen can be useful in guiding audience reactions: the warmth (Jane Wyman) or coldness (Lana Turner) of a particular actress, the reserved stiffness of an actor (Rock Hudson) or playing against type (Robert Stack)—these choices are strategically used to build audience response.

WIH: You teach classes on a variety of film topics including the Nazis’ effective use of propaganda in film between WWI and throughout WWII. I’ve read recently that China has been pulling back from screening Hollywood films in their cinemas in favor of their own Chinese filmmakers in order to control the narrative. Are there more current examples? Can this work both ways if filmmakers are subtle enough to get subversive messages across?

Prof. Frieden: Probably all countries—including ours—have at some point tried to control the messages going out in films. The early Soviets and the Nazis recognized and exploited the power of film to “capture the hearts and minds” of a population, and they created systems of control to manage what films were made and distributed. China and North Korea have as well. U.S. films during WWII did everything they could to emphasize patriotic support for the war cause—sometimes overtly, sometimes in more subtle ways, and with the support of the government (Why We Fight series by Frank Capra). 1950s science-fiction films in the U.S. featured creatures that were going to destroy our civilization and turn us all into (brainwashed?) zombies in the throes of the Red scare (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1956). More recently we’ve seen The Green Berets versus Apocalypse Now. In the U.S., it’s the marketplace that determines the films that are made. In earlier decades, we’ve seen films that demean and objectify women; now, we see Barbie.

WIH: What is it about German film in particular that has engaged you over the years?

Prof. Frieden: From early German cinema with its haunting Expressionist and Romantic imagery, to the harsh realism of 1930s Weimar films, to the Nazis’ use of love stories, costume dramas, science fiction/fantasy to mask their propaganda messages, to ex-pat directors fleeing Hitler for Hollywood (Douglas Sirk, Billy Wilder, Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang), to rebellious New German Cinema responding to post-war Germany with scorn and satire in their films, to Academy-Award winning films in recent decades—every new period of German cinema has been overwhelmingly gorgeous, challenging, and surprising so that there’s always more to see and enjoy.

Join us for Tearjerkers of the 1950’s: Films of Douglas Sirk, and explore the nuanced layers of Sirk’s films, uncovering their timeless resonance and profound impact on the cinematic landscape of the 20th century and beyond. Learn more and register HERE!